photo: ®Veronica Brown, Concern Rwanda program meeting

This Insight originally appeared on the Microfinance Gateway, and is published with permission.

About the Authors: This business case was a collaborative effort among all the named authors, all of whom are members of the Graduation Action Team subcommittee of the RESULTS Leadership Council. Bill Abrams is the President of Trickle Up. Joshua Goldstein is a Director of Fundacion Capital. Larry Reed is a Senior Fellow at RESULTS. Carine Roenen is Executive Director of Fonkoze. Jean-Francois Tardif is a Volunteer with RESULTS.

Executive Summary

To meet the ambitious Sustainable Development Goal to "end poverty in all of its forms everywhere" by 2030, it will be necessary to take intentional, focused, and effective steps to support the poorest and most vulnerable people. Based on more than a decade of development, research, and expansion, the Graduation Approach has demonstrated its potential to help millions start a sustainable route out of extreme poverty.

Graduation targets people who are well below the US$1.90/day threshold for extreme poverty – a cohort described as the “ultra poor,” “poorest of the poor,” “chronic poor,” “invisible poor,” and “destitute.” Their lives are characterized by food insecurity, poor health, minimal education, unreliable incomes, low social capital, and a lack of assets and land ownership. Daily, they face the risks of health crises, climate change, and other shocks and stresses. They often live "off the grid"; in remote rural areas, lacking access to banks and other financial systems, and are often excluded from poverty programs through governments or non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The number of people living in these unacceptable conditions of poverty is estimated to be in the range of 400-500 million (80-100 million families).

This is the moment to invest in Graduation. It provides a proven means of reducing extreme poverty and can increase the effectiveness of government social protection programs for the poorest and most vulnerable populations.

Graduation is defined by its five core characteristics: it targets the household , often those headed by women; it is holistic in that it combines social assistance, health care, livelihood training, and financial services; it provides the family an initial economic 'push' through a single, significant investment; it includes forms of coaching or mentoring to overcome economic and social barriers; and it is time-bound, with a clear schedule for graduating the household into larger social protection systems or access to microfinance.

To be sure, Graduation is not appropriate for every person living in conditions of extreme poverty but a reasonable estimate is that it could benefit some 200-250 million people. Graduation builds individual autonomy and agency, reduces the risk of long-term dependency on government programs, and can prevent downstream social problems exacerbated by poverty. Graduation connects marginalized citizens with the market and other financial, social, and political systems that can accelerate their progress. A growing body of evidence shows that Graduation can yield a very positive long-term return on an initial time-bound investment.

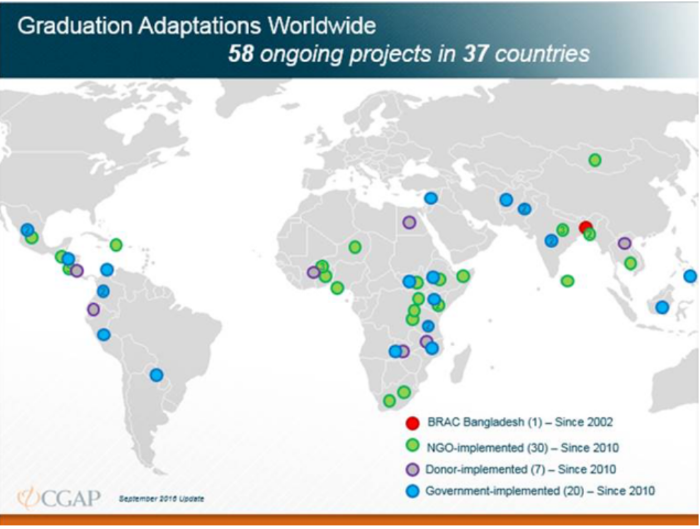

Graduation is at the cusp of breakout scaling. It is now being applied in 37 countries – 20 through government programs. Graduation initiatives have produced an impressive evidence base and a range of implementers are developing new ways to deliver and adapt the Graduation approach. A global network of implementers, policy makers, multilateral organizations, researchers, and funders are partnering for the purposes of continuous improvement in program design and delivery, cost efficiency, innovative financing and government adoption.

This paper presents the case for scaling Graduation such that it can make a significant, measurable contribution to achieving the global goal of ending extreme poverty by 2030. We address (i) why Graduation is effective, (ii) the potential for scale, (iii) the nexus between Graduation and social protection programs worldwide, (iv) the costs and cost-benefit of Graduation, and (v) how governments, funders and others in the development community can mobilize to bring the benefits of Graduation to millions of families.

Why Graduation is Effective

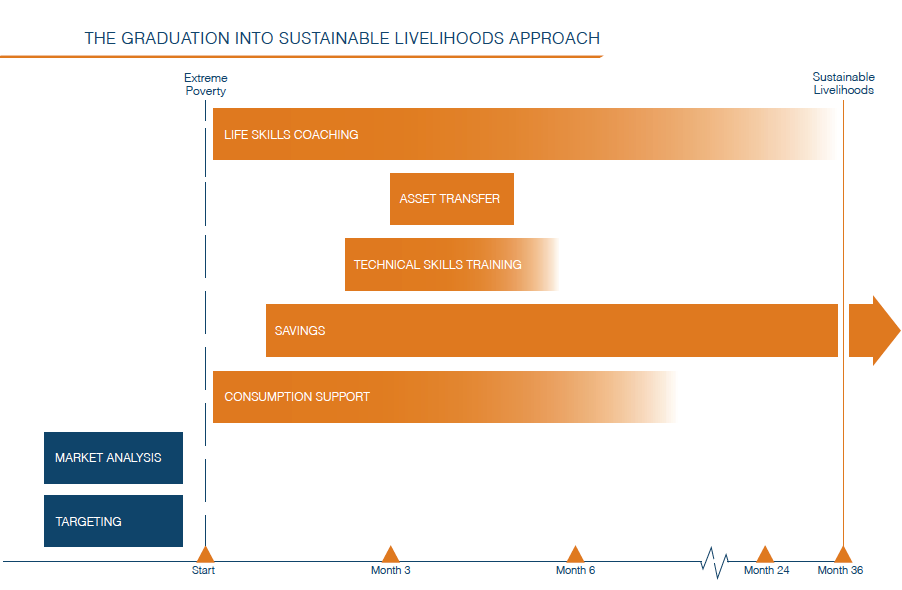

Graduation programs, developed initially by BRAC in Bangladesh and now adapted to sites on three continents, target the poorest households to help them "graduate", becoming autonomous economic participants in society, providing for their own families, and helping their children gain the health and education resources that can break the cycle of intergenerational poverty. Graduation programs vary by context but generally include elements of social protection, livelihoods development, and financial inclusion to combine support for immediate needs with longer-term human capital investments (Figure 1). Graduation interventions, typically over 2-3 years, commonly provide households with:

- Consumption stipends to ensure food security until sustainable livelihoods can be developed;

- Technical skills training focused on managing livelihood activities that are relevant and profitable in local markets;

- Cash or asset transfers to kick-start self-employment activities or training to link with formal job market opportunities;

- Cash or asset transfers to kick-start self-employment activities or training to link with formal job market opportunities;

- Access to savings and credit , plus financial education; and

- Regular home-based coaching visits for monitoring, building life skills and confidence and providing health, nutrition and other information.

FIGURE 1: Core Elements of the Graduation Model (Source: CGAP, 2016)

Graduation programs have been proven to effectively identify the very poorest and enable them to build sustainable livelihoods.(1)(2) In a landmark paper published in Science in May 2015, the results of randomized control trials involving 21,000 participants in six countries (Ethiopia, Ghana, Honduras, India, Pakistan, and Peru) provided compelling evidence that Graduation is cost-effective and leads to statistically significant and sustainable gains in economic and social outcomes for households in ultra-poverty across diverse contexts.(3)

Key outcomes included:

- Broad and lasting economic impacts. Household consumption, food security, asset holdings and savings increased, with positive effects lasting at least one year after participants completed the program;

- Increases in self-employment income. The combination of productive assets and relevant skills training led to an increase in entrepreneurial activities;

- Improvements in psychosocial well-being: Happiness, stress, women’s empowerment and some measures of physical health and political engagement improved; (Columnist Nicholas Kristof of The New York Times on May 21, 2015 highlighted “the power of hope” in lifting people out of extreme poverty);

- Effectiveness across multiple contexts and implementing partners. Positive results were not confined to a specific setting or location, suggesting that households in ultra-poverty face similar constraints in different countries;

- Positive cost-benefits. Calculations confirm that long-run benefits for people living in ultra-poverty outweigh the programs & up-front costs (4) (see Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab and Innovations for Poverty Action, Building stable livelihoods for the ultra-poor, for a summary of the Science article).

Other research by BRAC, the Massachusetts Institute of technology, and the London School of Economics on the long-term impacts of Graduation demonstrates positive effects on consumption, savings, ownership of land and other assets, diversification of income sources, and resilience to shocks.(5)(6)(7) Compared to a control group, such gains grow over time, and there is evidence that they continue to accumulate as much as seven years after participants graduate from the initial Graduation program. In India, households consumed 12 percent more than the control group after three years, and 25 percent more after seven years. In Bangladesh, households consumed 2.5 times more than the control group after seven years.(8)

Potential to Scale

Estimates vary as to the number of people living in conditions of profound poverty and vulnerability. The World Bank estimates that 767 million people (11 percent of the planet’s population) live on less than US$1.90/day, with the majority struggling to survive on far less. (9) The Oxford Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) puts the number of extreme poor at 1.6 billion, with about one-third (465 million) suffering severe deprivation.(10) The Chronic Poverty Research Center has estimated that 336-477 million people live in sustained, multigenerational poverty; roughly equivalent to about 60 percent of those living in “extreme poverty”.(11) Given an estimate of five people per household, the scale of the challenge encompasses about 80-100 million households.

Whatever number, it is too large. Graduation, a household-level intervention, presents a pathway for millions of families to live a more secure and dignified life but there are, of course, limitations. Graduation is not suitable for all people living in ultra-poverty; the aged, those without the capacity to work, for instance. Graduation should not be viewed as a substitute for employment where jobs are available. Given these caveats, the theoretical potential “market” for Graduation is some 200-250 million people. Thus, the number of households where Graduation could make a difference (40-50 million) is well within the world’s resources and one’s imagination.

Graduation has reached an estimated 2.5 million households to date, generally through smaller-scale projects. (12)

It has reached a trigger point for accelerated scaling that makes reasonable a goal of helping tens of millions of households by 2030. Catalysts for that transformation include:

- A strong evidence base demonstrating its effectiveness and cost-effectiveness;

- Adoption of the Graduation Approach by 20 governments (Figure 2), with significant potential for expansion within those countries and adoption by other governments;

- A growing, well-organized community of practitioners and researchers that is setting best-practice standards and can provide technical assistance to governments and implementing agencies;

- The imperative of UN Sustainable Development Goal, adopted by 193 nations, to “leave no one behind”.

FIGURE 2: Global Graduation Activities and Implementations

The Nexus Between Graduation and Social Protection

The largest single potential force for scale is the nexus between Graduation and social protection safety net programs.

Over the past two decades, governments in developing countries have embarked on safety net programs aimed at providing a range of essential services to people living in poverty in their countries. Rather than solely providing safety nets, however, governments sought to build more coordinated approaches that could reduce “…the economic and social vulnerability of poor, vulnerable and marginalized groups”.(13) Safety net programs take many forms; the largest are cash transfers that can come with conditional requirements (e.g., linked to vaccinations or school attendance) or straight payments without conditions.

Two pioneering approaches – Bolsa Familia in Brazil and Prospera (formerly Oportunidades) in Mexico – produced impressive results and inspired many adaptations and variations around the world. Today Bolsa Familia reaches 12 million families and Prospera 5.8 million families (one quarter of Mexico’s population), and more than 45 countries employ cash transfer programs to reach over 500 million individuals.(14) Drawing upon numerous studies, in 2011 DFID conducted a literature review that showed that cash transfer programs can lead to significant reductions in inequality and the depth or severity of poverty. For example, one study attributed a 28 percent decrease in Brazil’s GINI coefficient (a summary measure of inequality) from 1995 to 2004 to the cash transfer programs implemented by the government.(15)

However, cash transfer programs have not been as effective among the poorest. Simply put, the poorest need more than money. Cash transfers can limit the severity of their poverty but do not provide sufficient resources to help them move out of poverty. Those living in chronic poverty “have fewer options, less freedom to take up available options, and so remain stuck in patterns of life which give them low returns to whatever few assets they have maintained”.(16) In short, “To support graduation from poverty, cash transfers needs to be linked to livelihood development”.(17)

It is the intersection of the Graduation Approach and cash transfer programs that creates the opportunity for dramatic scale. Graduation provides a proven strategy for movement away from poverty. Cash transfer programs provide enormous resources to fund Graduation, have already established a means to reach large numbers of people, and demonstrate that the political will already exists to serve the poorest and vulnerable citizens.

Cost… and Cost-Benefit

Graduation is not a low-cost intervention. Its two main components – an asset transfer or cash grant to help jumpstart a livelihood, plus regular training and coaching visits – are critical factors for success but clearly require significant resources. By one estimate, the average cost of Graduation was found to be US$1,148 per household over the course of the 18- to 24-month program (i.e. around US$200 per beneficiary), with actual costs of each program differing widely across sites due to variances in staff salaries, cost of inputs and population density.(18)

However, when tied to cash transfer programs that already have been funded, the incremental cost of the robust Graduation Approach is considerably smaller. In two large states in India, for example, Trickle Up has found that when the Graduation Approach is sequenced with, and supplemented by, existing government programs that contribute key inputs, cost increases are incremental and modest. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) — a UN agency mandated to protect and support refugees — is also recognizing the Graduation Approach’s potential to help refugees living in rural areas, urban centers, and refugee camps.(19)

Many of the components of the Graduation Approach are already found in UNHCR operations, though typically they are not combined, sequenced, or time-limited to meet the needs of the poorest people. Applying a “Graduation lens” to its operations helps UNHCR to carefully sequence its existing interventions so that the poorest refugees who qualify for Graduation receive appropriate support at the right time in their development; cash assistance in the early phase as participants get their footing and participate in skills training activities, a seed capital grant or job placement to boost their income, and individualized mentoring throughout. Given that the Graduation Approach builds on existing services provided and facilitated by UNHCR and partners, there is only a marginal and modest additional cost to adopting the approach.(20)

The ultimate test for any poverty intervention is not absolute cost, however. The real question is one of cost-benefit. Do the long-term economic gains by households materially exceed the cost? Evidence from India and Bangladesh show that benefits in the lives of the recipients have greatly exceeded costs:

- In Bangladesh, four years after the start of the program, increased consumption by participants equaled 240 percent of program costs.

- In India, based results over three years, the estimated net present value of future impacts equaled 430 percent of program costs.(21)

- In a review of projects across six countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, researchers estimated the benefits from increased consumption and asset growth equaled 166 percent of the costs of the programs.(22)

Importantly, the benefits continue to grow. In both India and Bangladesh, participants were still experiencing higher levels of consumption seven years after receiving the transfer of an asset.(23)

A recent report for the “Access to Finance Forum” compared cash transfer programs, livelihood programs, and the Graduation Approach. It found the cash transfer programs to be the most cost effective but found little evidence of their long-term impact on those in extreme poverty. The report concludes: "Based on available evidence, the Graduation Approach is the clearest path forward to reduce extreme poverty in a sustainable manner."(24)

Additional gains, including social benefits and reduced government expenditures, represent another dimension of the cost-benefit analysis of the Graduation Approach. While difficult to quantify, they include:

- Avoiding costly downstream problems engendered by extreme poverty such as alcoholism, teen pregnancy, and truancy

- Increasing resilience, thus reducing the need for costly emergency response activities

- Raising tax revenues for governments, as a result of increased household consumption

- Reduced support payments over time, as people become more self-sufficient (In Kenya, the BOMA Project intervention costs US$283 per person over two years, whereas common food aid is about US$392 per person over the same period (25))

- Increasing integration (through inclusive Graduation models) of historically excluded individuals into the economy, such as persons with disabilities

Catalyzing Global Progress on Ending Extreme Poverty

To be sure, reaching scale will require significant effort across several aspects of work: continuous improvement and innovation of Graduation methods; investment in the systems and people needed to expand by an order of magnitude; careful evaluation of positive and negative impacts (e.g., will markets become saturated?); and a deeper understanding of how the catalytic benefits of Graduation must be accompanied by improvements in schools, health care, and other institutions that meet people’s basic needs.

In a world riven with the effects of growing inequality, Graduation promises the opportunity to change direction and create a system where all, no matter what their starting point, can provide for themselves and invest in a better future for their children. The global community has set this as its common target by approving the Sustainable Development Goals, which call for the end of extreme poverty by 2030. In order to reach that goal, we must begin investing now in proven strategies for reaching the hardest cases, those who have lived their lives in chronic poverty.

Now is the time to invest in Graduation. It has the potential to improve the futures of 200-250 million people who struggle to survive every day. They cannot be neglected or overlooked, especially as the world seeks to accelerate the historic gains in poverty reduction over recent decades and to eliminate extreme poverty by 2030. The Graduation Approach, developed and refined in dozens of settings over the past 15 years, has demonstrated its validity. It is supported by an engaged, well-organized community-of-practice. And there is a compelling and cost-efficient path to scale by linking Graduation to existing cash transfer and other relevant safety net programs. It is ready to scale.

Notes

- Karishma Huda and Anton Simanowitz, “A Graduation Pathway for Haiti’s Poorest: Lessons Learnt from Fonkoze,” Enterprise Development and Microfinance, 20, no. 2, (June, 2009), 86-106.

- See “Targeting Efficiency”.

- Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Nathanael Goldberg, Dean Karlan, Robert Osei, William Parienté, Jeremy Shapiro, Bram Thuysbaert, and Christopher Udry. “A Multi-faceted Program Causes Lasting Progress for the Very Poor: Evidence from Six Countries.” Science, 348, no. 6236, (May 15, 2015): DOI: 10.1126/science.1260799.

- “Building stable livelihoods for the ultra-poor,” Policy Bulletin, Innovations for Poverty Action, September 2015.

- Oriana Bandiera, Robin Burgess, Narayan Das, Selim Gulesci, Imran Rasul and Munshi Sulaiman. “Can Basic Entrepreneurship Transform the Economic Lives of the Poor?” The London School of Economics and Political Science, April 2013.

- “Pioneering programme helps households climb out, and stay out, of extreme poverty,” International Growth Center, December 9, 2015.

- “Leaving it behind: how to rescue people from deep poverty – and why the best methods work,” The Economist, December 12, 2015.

- Allison Fahey and Justin Loiseau, “Ending Extreme Poverty: New Evidence on the Graduation Approach,” Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP), 22 November 2016.

- “Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2016: Taking on Inequality: ,” World Bank, 2016.

- “Multidimensional Poverty Index,” Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative, Oxford University, 2016.

- Andrew Shephard, “Tackling Chronic Poverty: The policy Implications of research on chronic poverty and poverty dynamics,” Chronic Poverty Research Center, 2011.

- Syed M. Hashemi and Aude de Montesquiou, “Graduation Pathways: Increasing Income and Resilience for the Extreme Poor” Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP), December 12, 2016.

- Stephen Devereux and Rachel Sabates-Wheeler. 2004. Transformative social protection. Working Paper 232. Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK.

- Sridharan, Vishnu. 2012, July 9. Emerging voices: Vishnu Sridharan on cash transfers and financial inclusion.

- Jens M. Arnold and João Jalles. 2014. Dividing the pie in Brazil: Income distribution, social policies and the new middle class. Working paper 1105. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Accessed May 26, 2017.

- David Hulme, Karen Moore, and Andrew Shepherd. 2001. Chronic poverty: Meanings and analytical frameworks, Chronic Poverty Research Centre Working Paper. Accessed May 28, 2017.

- Ibid, ii

- Munshi Sulaiman, Nathanael Goldberg, Dean Karlan, and Aude de Montesquiou. Eliminating Extreme Poverty: Comparing the Cost-Effectiveness of Livelihood, Cash Transfer, and Graduation Approaches, Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) and Innovations for Poverty Action, December 2016.

- UNHCR, in partnership with Trickle Up, has been piloting Graduation since 2014 in Burkina Faso, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Egypt, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. UNHCR aims to implement an additional 15 Graduation programs by 2018.

- Ziad Ayoubi, Syed Hashemi, Janet Heisey, and Aude de Montesquiou. 2017. “Economic Inclusion of the Poorest Refugees”.

- Fahey and Loiseau.

- Abhijit Banerjee et al.

- Fahey and Loiseau.

- Munshi Sulaiman, et al.

- Colson K. Unpublished - 2016